Award of Excellence: Chernobyl

Caption

Slide 7 of 10

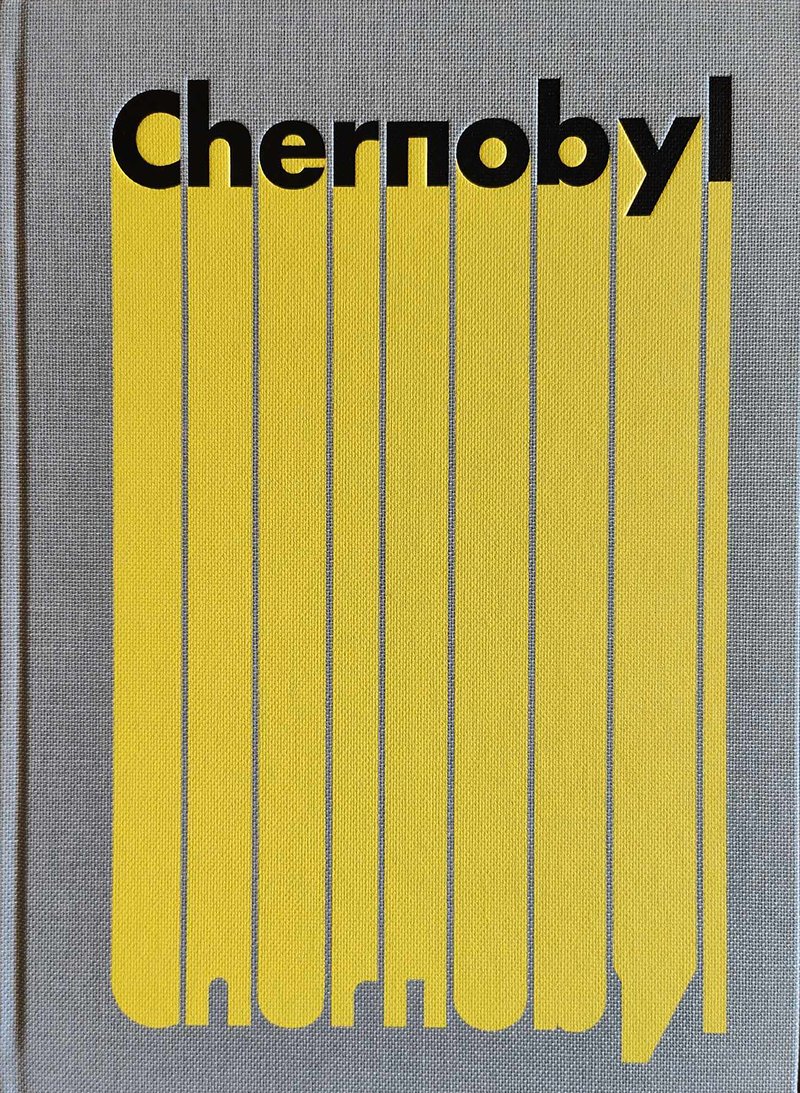

Chernobyl

May 2, 2024

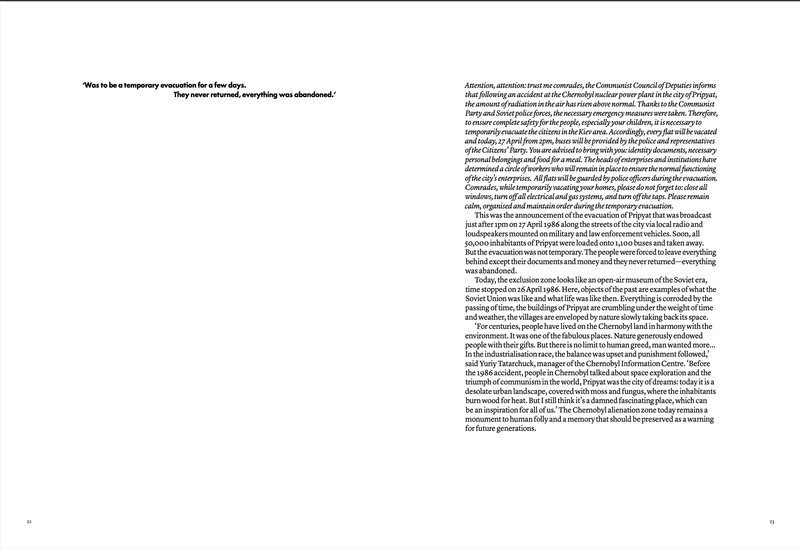

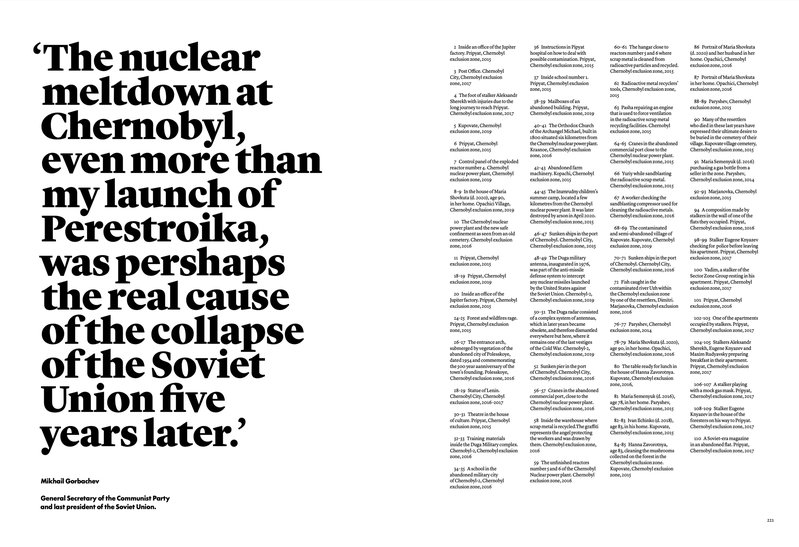

pages 78-79 The last legal inhabitants of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, the so-called samosely resettlers now number less than 200. Like Hanna Zavorotnya, eighty-three years old, or Maria Ilchinko, seventy-nine years old. Most of the surviving elders are women, traditionally called babushkas or grandmothers, but there are also men like Viktor Petrovich Lukanjenko, seventy-five years old. They live scattered in the semi-abandoned villages of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, surviving as they have always done, with the products of the garden and what nature offers them, but virtually in almost total isolation. No infrastructure, no transportation connects them to civilization, only some officials of the exclusion zone who occasionally check to see that everything is in order, and their children who live outside the zone who periodically come to visit them. When the Chernobyl exclusion zone was created by the Soviet government after the Chernobyl nuclear accident, 116 thousand people were evacuated and transferred to the outskirts of the big cities. The area was too contaminated to allow the population to live there. But some, about 1,200 people, decided that life in cities was not for them—too difficult to survive with poor wages and without the products of the garden. And above all, their bond with the land was too strong to abandon it forever. When the last of the survivors die, the village culture in the province of Polessie, with its history, traditions and customs, will end.

Pierpaolo Mittica